When I first started painting with the Ozark pigments, I wasn’t sure yet whether I would be able to make good art with a handful of colors. It’s a very limited palette of earthy tones ranging from white to black, with yellow, green, red, brown in between. Some of the colors won’t blend, so I use them as they are. Others I blend with limestone to vary the shades. I think I’ve figured out how to make this work, at least with watercolors.

The year 2023 marks the beginning of my journey with Ozark pigments in oils, and I’m pretty excited to get started. (Note: I found that I couldn’t make white with our native pigments. Limestone just makes a sheer white. So I’ve begun outsourcing titanium to make white.) I’ve found that I can make a fairly lightfast blue from indigo pigment, so I’ll grow woad in 2024 for that. And thyme makes a good lightfast yellow lake pigment. So I’ll have green by combining those two.

A Limited Palette

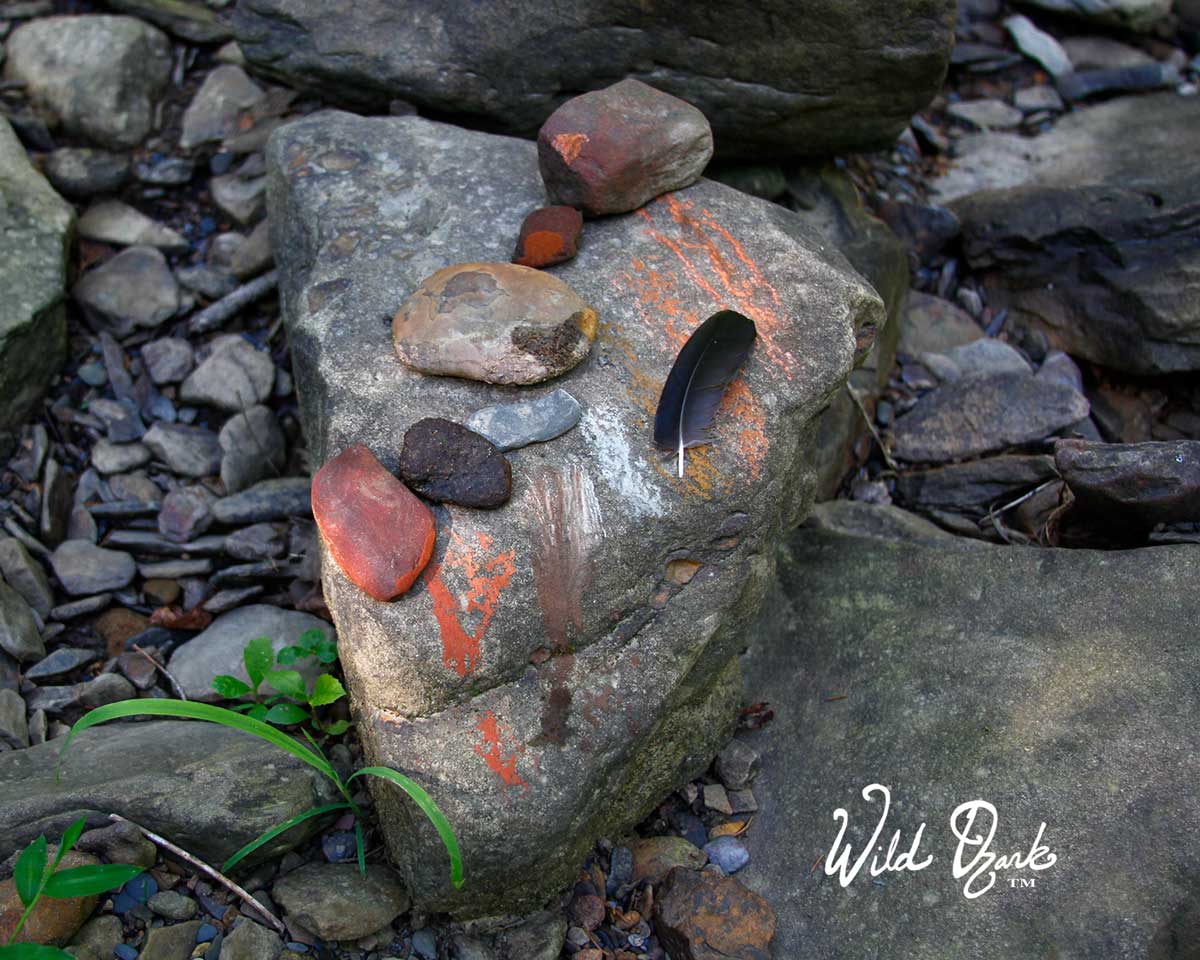

I gather the raw materials for the pigments from the land here at Wild Ozark. Some of them come from the driveway, some from the creek, and others are found randomly around the property. Some of the certain rocks I need come from the creeks and river just beyond our property. Examples of this would be limonite (yellow) and small little chunks of red.

Other things I collect for pigment sources include antler sheds, or antlers from Mr. Wild Ozark’s hunting successes, soot from the wood stove, and bones.

Bones, you say? Lots of people have cows around here, and there’s often a bounty of bleached bones to be found. Then again, I can use bones from hubs’ hunting successes. A limited palette doesn’t necessarily mean my resources are limited. In fact, it’s quite the opposite. There are copious rocks, bones, and soot to be found here, at least.

Local Pigments

By ‘local’ in this case, I mean local to the scene I am going to paint. So far, I’ve only painted scenes and wildlife that are local to Wild Ozark. So I’ve only used pigments gathered here in Madison county, Arkansas. But while I have a palette limited to local pigments, it doesn’t mean that I can’t collect colors from other places and use them to paint the scenes of those places. Eventually, that’s exactly what I’ll do. I’ve already gathered a few sets of raw materials. When I spent time with a friend in Stephenville, TX, I gathered a bunch of oak galls that will lead to a nice monochrome painting of a scene from that area one day.

And while hubs and I were in Colorado near Lake Jefferson, I gathered a bone and another various rocks.

Now, those rocks are a lot harder than our rocks and I’m not sure if it will make good pigment. Aside from those, I have sand that I gathered while in Qatar a few years ago. It’ll have to be a monochromatic painting on dark paper, but should be able to do that.

From Raw Material to Paint

Once the materials are gathered, there’s a process to make the paint. Until the very end, it doesn’t matter what kind of paint I’m making. It’s the same for everything – first I need to get the pigments in the form of a fine dust. The palette may be limited, but the variations on what I can do with those colors seems wide open.

Rocks

First the rocks need to be broken into smaller pieces. I use a hammer, or a larger rock for that. When the pieces are small enough, I run them through my rock crusher to make a powder. But the powder is still too gritty to go directly to making the paint, although if I want a rough paint, I can do it. Usually I wash the pigments next.

The heavier grit falls to the bottom and I drain off the colored water and let it settle. Once it’s settled I’ll pour off the cleared water and let the sediment dry. That is the part I call ‘lites’. And it is the part that leads to a smooth paint. After the sediment dries, I’ll crush it again and then make the paint. Crushing it is easy this time, though, because it’s just a powder cake. Just becaues it’s a limited palette, that doesn’t mean the process is any more limited.

When I use a limestone rock, I can’t use the crusher. And that’s unfortunate, because the limestone is one of the hardest rocks to reduce to powder. It looks all chalky and crumbly, but looks would be deceiving, ha. I have to break that one with a hammer, then continue to pummel the smaller pieces in a porcelain mortar/pestle, and grind it as much as possible with that same mortar/pestle. Then I can wash the pigment and get the finer white.

Soot

When we clean our chimney, I gather the soot that falls down into the wood stove. This is pure carbon black, and it will make a really deep black paint. But it’s a flat black, with no sheen. Once the soot is gathered, I crush it in a mortar and pestle. Then it, too, gets washed. For a black with a sheen to it, there’s a black rock that I use, but it’s not easy to find. So for the most part I use soot and bone for black. If I used only rocks for my paints, then my limited palette would be close to the same as when I’m using soot and bone, too. But I like having multiple sources whenever I can.

Bone and antler

Before I can reduce the bones to powder, they have to be charred. I can do that either in the woodstove or in my kiln. I have a new little crucible to try it in the kiln, but I haven’t used that method yet. All of the bone black I’ve made so far, I made by charring it in the woodstove. Once the bones have been charred and are fully black throughout, then I’ll crush them first with a hammer and then again in the mortar and pestle. And then they, too get washed. Antler is treated in the same way, except I can easily cut the antlers into smaller pieces with a scroll saw before I char them. I am going to try that with the bones next time, too.

The flat, velvety black of soot, antler and bone adds a visual dimension to the black available in my limited palette of rock pigments.

Donated Rocks

In addition to the rocks I’ve gathered myself, I also have rocks from all over the world that awesome friends and followers who have mailed to me! I’ve got some from Alabama, Washington State, other parts of Arkansas, and even from an Icelandic glacier, and the Virgin Islands (my favorite so far!). There are others too that I just can’t remember off the top of my head. Oh I just hope I live long enough to try all of these collections out, haha. I’m not sure one lifetime is going to be long enough for all of the things I want to do. But one thing is for sure – I will never be bored.

Wrapping Up

Now that I’ve gathered the pigment sources and reduced them to powders, I can make the paint. And this is the part where the roads divide, depending on what kind of paint I’ll be making. For watercolors, I’ll mull the pigment into a binder made of gum Arabic, honey, and water. But to make an oil paint, I’ll mull the powder into a drying oil. I’ll make another post later once I start making my next set of oil paints for 2023. Thanks for reading!

ABOUT

________________________________

Madison Woods is the pen-name for my creative works. I’m a self-taught artist who moved to the Ozarks from south Louisiana in 2005. My paintings of Ozark-inspired scenes feature lightfast pigments from Madison county, Arkansas. My inspiration is nature – the beauty, and the inherent cycle of life and death, destruction, regeneration, and transformation.

Roxann Riedel is my real name. I’m also salesperson for Montgomery Whiteley Realty. If you’re interested in buying or selling in Madison or Carroll county, AR, let me know! You can see the properties that I blog about at WildOzarkLand.com.

Wild Ozark is also the only licensed ginseng nursery in Arkansas. Here’s the link for more information on the nursery

P.S.

There’s always a discount for paintings on the easel 😉

Here’s my Online Portfolio

And, Click here to join my mailing list.

Contact Mad Rox: (479) 409-3429 or madison@madisonwoods and let me know which hat I need to put on 🙂 Madison for art, Roxann for real estate, lol. Or call me Mad Rox and have them both covered!

https://www.youtube.com/@wildozark

Leave a Reply