When I want a certain color of paint, I’ll go to the creek to look for the rocks I’ll need. In this case, the color is a rich russet – brown with orange influence. What is the color story behind the rocks?

But that’s not really where the color story starts. The story starts when the rocks first gained their colors. Why are some rocks one color and another is different, even though they’re lying side by side in the creek? What gives each rock its color?

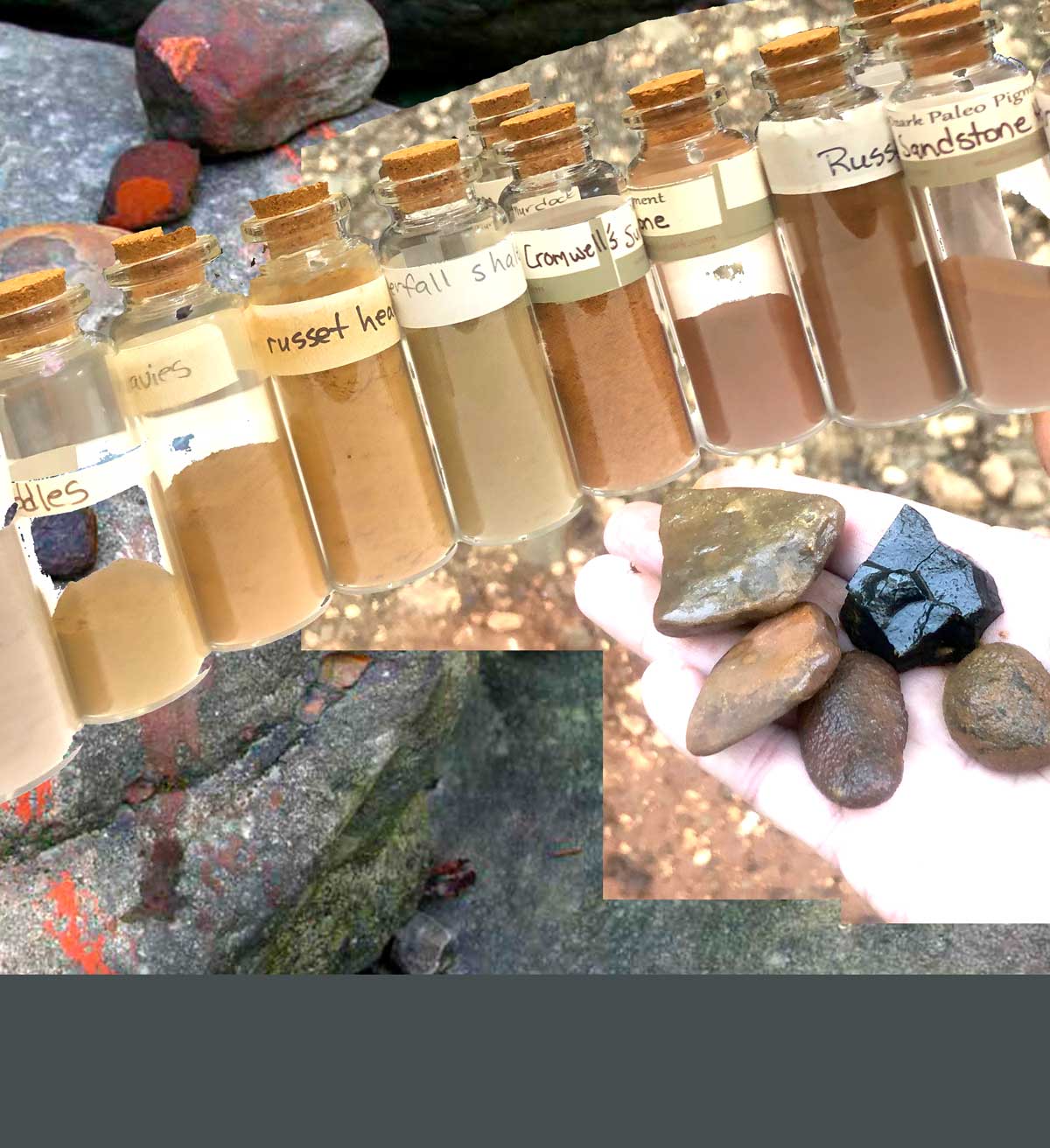

The Wild Ozark Rocks

Our rocks are mostly sedimentary: sandstone, siltstone, and shale. This changes abruptly from hill to hill and creek to creek out here in northwest Arkansas, though. As the crow flies, less than a mile away, the hills are mostly limestone and chert. It makes a difference if I’m looking for pigments. Sandstones, siltstones, and shale are where almost all of my Paleo Paints are sourced.

When it comes to sandstone color stories, all of the shades it comes in is caused by varying combinations of iron, and sometimes manganese with oxygen. So basically, rust. Rusty rocks. The shades of red come from the iron oxides, and the purple comes from manganese oxides. But what about the yellow and tan? Those, too, are from iron oxides, it’s just that the iron has been oxidized to different degrees. I learned an interesting thing about turning yellow sandstone to red through the use of high heat. I haven’t tried this yet, but it’s on my list of things to experiment with, eventually. It takes a fairly hot fire to get the 800 or so degrees needed.

Our shale is almost always gray. But there’s a greenish-gray stone I’ve found and I can’t tell if it’s shale or siltstone, or what. It seems to have similar properties to a shale so that’s how I’ve tentatively categorized it. Shale is made of clay that settled in thin layers before it compressed into stone. The gray shale crumbles fairly easily, but the greenish one is still pretty hard no matter how wet or dry it is. Another difference between the gray and the green is odor. The gray one smells of sulfur if I don’t wash it before making the paint. The green one does not.

Next Chapter in the Color Story: From Rocks to Pigments

Once the rocks are identified and gathered, I grind them using a mortar and pestle. To break them smaller before the mortar, I just put them between larger rocks and crush them a little bit that way first. I’m excited to try a new way of crushing the rocks soon, though. Rob bought me a prospector’s rock crusher for my combo birthday-anniversary-christmas gift and by early next year we should have this nice little machine installed.

Once the rock is ground to a coarse powder, if I want to have a smoother paint, I’ll wash the pigments. All the powder is placed in a large jar and then I add water. Shake well and pour off the colored water, leaving the heavier sediment behind. The heavier sediment left behind is called ‘heavies’.

The pigment dispersed in the water that was poured off will settle eventually to the bottom of the jar. Once the water has cleared, I’ll pour it off and save the sediment. This part is called the ‘lites’ or ‘lights’. This part makes a very smooth paint.

Sometimes the two layers are significantly different in the color shades, but often they are the same. Either way, the heavies can be ground again and the resulting paint will be coarser and have more granulation. The lites are often very rich in pigment and perform well in washes.

Russet is one of the pigments that will stain the paper, so it is usually there to stay once you put it down.

As you might expect, the color comes mostly from iron oxides, as is the case with most of the pigments here in the Ozarks.

References

https://www.geology.arkansas.gov/geology/general-geology.html

ABOUT

________________________________

Madison Woods is the pen-name for my creative works. I’m a self-taught artist who moved to the Ozarks from south Louisiana in 2005. My paintings of Ozark-inspired scenes feature lightfast pigments from Madison county, Arkansas. My inspiration is nature – the beauty, and the inherent cycle of life and death, destruction, regeneration, and transformation.

Roxann Riedel is my real name. I’m also salesperson for Montgomery Whiteley Realty. If you’re interested in buying or selling in Madison or Carroll county, AR, let me know! You can see the properties that I blog about at WildOzarkLand.com.

Wild Ozark is also the only licensed ginseng nursery in Arkansas. Here’s the link for more information on the nursery

P.S.

There’s always a discount for paintings on the easel 😉

Here’s my Online Portfolio

And, Click here to join my mailing list.

Contact Mad Rox: (479) 409-3429 or madison@madisonwoods and let me know which hat I need to put on 🙂 Madison for art, Roxann for real estate, lol. Or call me Mad Rox and have them both covered!

https://www.youtube.com/@wildozark

Leave a Reply